In music, chords are often the way performers or composers would create harmony in their songs.

The way we play those chords tells us many different things about them and about the harmony at that specific moment. Chord inversions are useful in helping us understand how and why a chord is played a certain way.

In this post, we’ll learn all about chord inversions and how they work. But first, let’s look back at what a chord is.

What Is A Chord?

In music, a chord is when two or more notes (also called pitches) are played at the same time. We can categorize chords into a few different types depending on how many notes they have. We can have them in

- groups of two notes, which are called intervals or dyads;

- groups of three notes, which are called triad chords; and

- groups of four or more notes, which are usually referred to as seventh chords or extended chords.

Triads, seventh, and extended chords often are built from a scale.

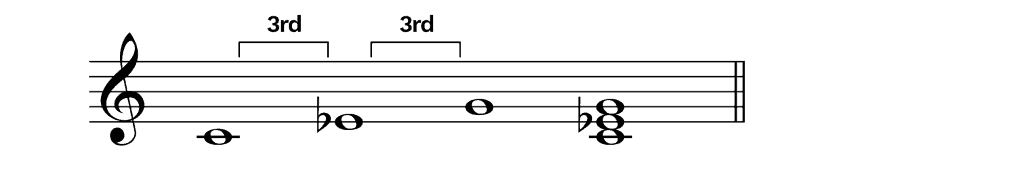

A triad takes the root, or first note, of the scale, the third scale degree, and the fifth scale degree, with each interval being a third.

For example, C minor scale has the notes C – D – Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb – C. You take the first, third, and fifth notes (C – Eb – G) to make a C minor triad.

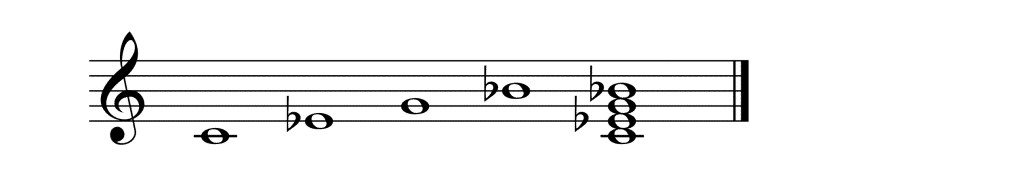

A seventh chord uses the root, third, fifth, and seventh scale degrees, so a Cmin7 chord would add the Bb (C – Eb – G – Bb).

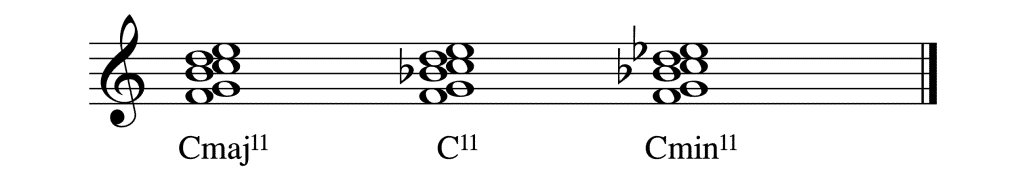

Extended chords add the 9th, 11th, and 13th scale degrees, which are octaves of the second, fourth, and sixth, respectively.

If you need to learn more about all the different types of chords, check out our post on chords here.

What Is A Chord Inversion?

Up until now, all the chords we’ve been talking about have started on the root note, which is the same note as the name of the chord.

The starting note is the one that is the lowest in the chord, and then the others build up on top of it. For example, if you have a Gmaj7 chord, you know the lowest note in the chord is the note G.

However, triads have three notes, seventh chords have four, and extended chords can have up to six!

What if you wanted to start a chord on a note besides the root?

When you have a chord where the lowest note isn’t the note that the chord is named after, then this is what we call a chord inversion.

A chord inversion takes a different starting note (also called the bass note) and builds the chord up from there.

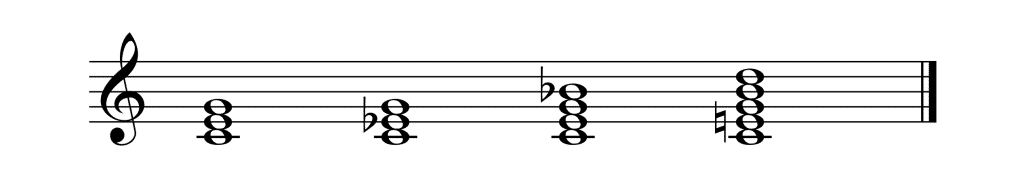

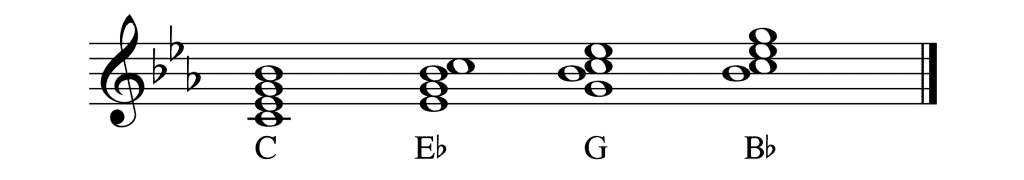

Let’s take the Cmin7 chord that we listed above as an example. It has four notes, and it can start on any one of the four.

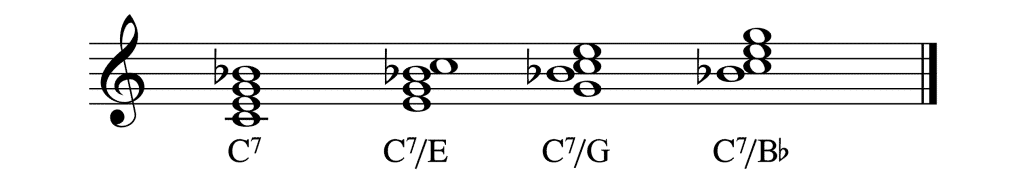

Here is a Cmin7 with each note (C, Eb, G, Bb) as the lowest:

Types Of Chord Inversions

Each of these types of chord inversion has a different name depending on which note is the lowest note in the chord.

Here are the names of the different inversions:

- Root position — The root is the lowest note

- First inversion — The third is the lowest note

- Second inversion — The fifth is the lowest note

- Third inversion — The seventh is the lowest note

You can also have fourth, fifth, and sixth chord inversions. We’ll touch on these briefly, too.

Root Position

When you see a chord that has its root note (the note that the chord is named after) as its lowest note, then this chord is in the root position. This means that it hasn’t been inverted, and so we don’t count it as a chord inversion.

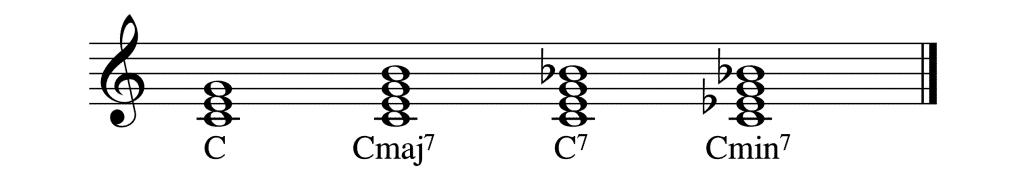

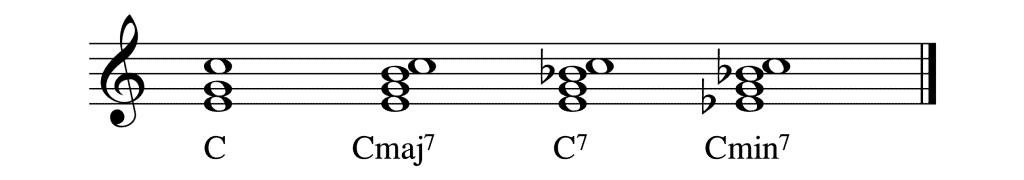

Here are multiple C chords (Cmaj, Cmaj7, C7, and Cmin) all in the root position. As you can see, they all start on a C:

First Inversion

A chord is in first inversion if the lowest note (bass note) is the third scale degree.

When writing out a chord, the third is usually written as the first note after the root (C – Eb – G – Bb), which is why starting a chord on this note is called first inversion.

To get a first inversion chord, you start with the bass note of the third and then stack the fifth, maybe seventh (if it’s there — remember triad chords only have root, third, and fifth), and then root.

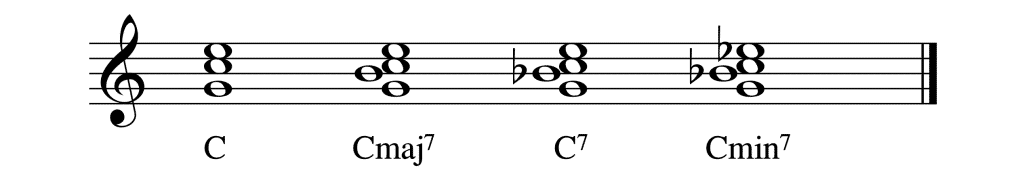

Here are multiple C chords (Cmaj, Cmaj7, C7, and C min) all in first inversion. As you can see, they all start on an E (Cmaj, Cmaj7, C7) or Eb (Cmin):

Second Inversion

A chord is in second inversion if the lowest note is the fifth degree of the scale.

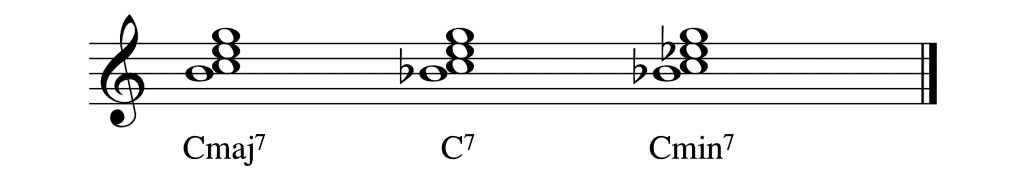

Here are multiple C chords (Cmaj, Cmaj7, C7, and Cmin) all in second inversion. As you can see, they all start on a G:

Third Inversions

A chord is in third inversion if its bass note is the seventh scale degree.

Here are multiple types of C seventh chords (Cmaj7, C7, and Cmin7) all in third inversion. As you can see, they either start on a B or Bb.

Fourth, Fifth, And Sixth Inversion

You can also have fourth, fifth, and sixth chord inversions. These use notes other than the root, third, fifth, or seventh note as their lowest notes.

These aren’t as common as the other types of chord inversion but are still worth mentioning as they do come up from time to time.

Fourth Inversion

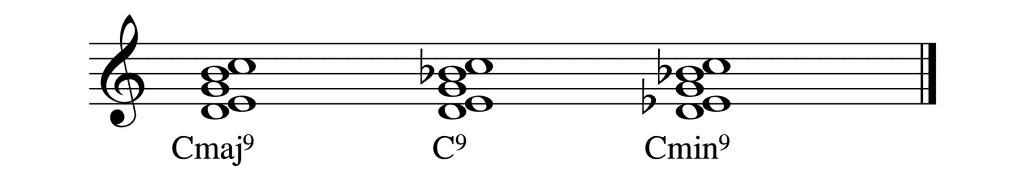

A chord is in fourth inversion if its bass note is a ninth. A ninth is just the second degree but an octave higher.

For example, here are some C extended chords in fourth inversion, and as you can see, they all start on a D.

Fifth Inversion

A chord is in fifth position if its lowest note is an 11th. An 11th is just the fourth degree but an octave higher.

Here are some C extended chords in fifth inversion; they all start on an F.

Sixth Inversion

Lastly, we have sixth inversion, which is where the lowest note is a 13th. A 13th is just the sixth degree but an octave higher.

In C, this would mean the lowest note would be an A.

Figured Bass Notation

Figured bass is a type of musical notation that helps us know what inversion a chord is supposed to be played or read in. It is used primarily in classical music.

In figured bass, little numbers appear immediately to the right of a chord that is in a specific inversion. There are different numbers for triads and seventh chords, however.

Triad Chord Figured Bass

For triads chords, there are three possible positions — root, first inversion, and second inversion.

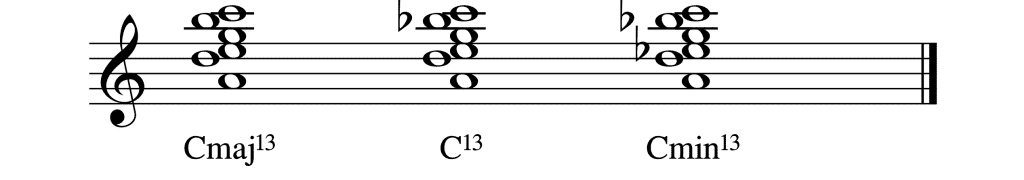

In root position, there are no numbers next to the chord:

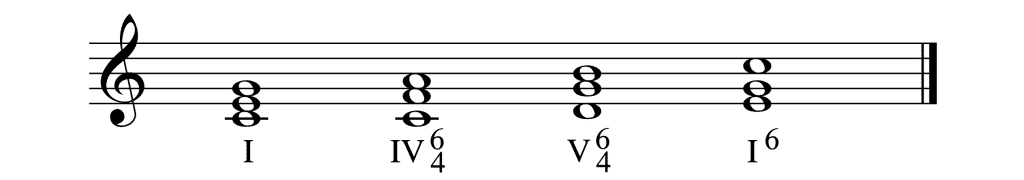

However, a chord in first inversion would have a little 6 to the chord, and a chord in second inversion adds a 64 to the chord.

I’ll change the inversions of the chords above to show this:

Seventh Chord Figured Bass

With seventh chords, things are a bit more tricky.

Again, in the root position, there are no numbers next to the chords. (Sometimes you would see a 7, like I7, but it’s not necessary).

However, in first inversion, the chord would be written as I65; in second inversion, the chord would be I43; and in third inversion, the chord would be I42.

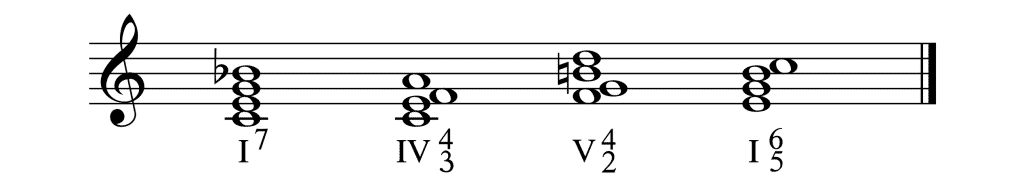

Here is an example of all the different positions using seventh chords of the ones shown above (C7, Fmaj7, G7, Cmaj7). See if you can tell which inversion each chord is in:

Slash Chords

In pop music, slash chords are the most popular way of writing chord inversions. This is simply a chord that tells you the bass note underneath it, separating the two with a slash ( / ).

For example, a second inversion C major chord would be written as G – C – E. A slash chord that tells us to play the C major in second inversion would be C/G. If it was in first inversion, the slash chord would be C/E.

A C7 chord root, first, second, and third inversion are as follows:

Slash chords aren’t only used for inversions because, theoretically, any chord can be played over any bass note.

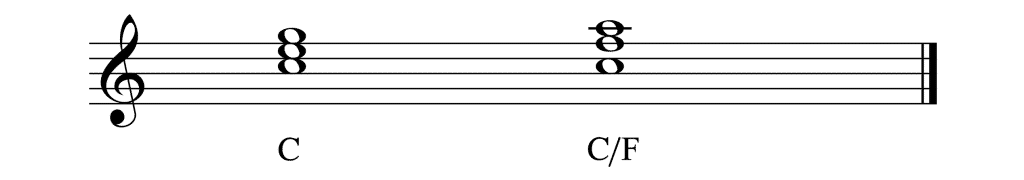

A C/F chord, for example, would just be a C major chord played over the note F (and notated as F – C – E – G). But for this article, we’ll just focus on slash chords used as inversion notation.

Related: Check out our guide to slash chords here.

When Are Chord Inversions Used?

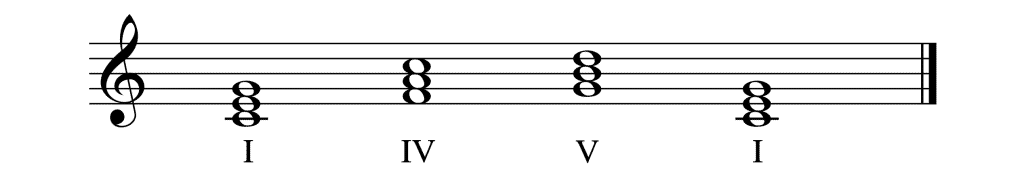

Chord inversions are predominantly used in order to facilitate easier voice leading through different chord progressions, especially in the bass.

For example, say you’re playing a I – IV progression. The fifth of the IV chord is the same as the root of the I chord, so if you played the fifth as the bass note of the IV chord (second inversion), you don’t have to move the root note from the first chord.

See it written in C here (Cmaj – Fmaj):

This song, “Us” by Regina Spektor, does this exact thing (also in Cmaj):

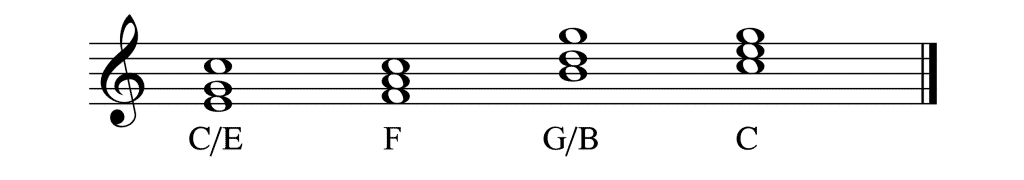

Also, the I chord in first inversion has the third as the bass note, which is one-half step below the root position IV chord.

Similarly, the first position V chord has a seventh as a bass note, one-half step below the tonic:

A song that uses the I chord in first inversion to lead to the IV chord is “Thinking Out Loud” by Ed Sheeran.

The song “Landslide” by Fleetwood Mac uses the V chord in first inversion to lead to the I chord.

Cadential 6/4

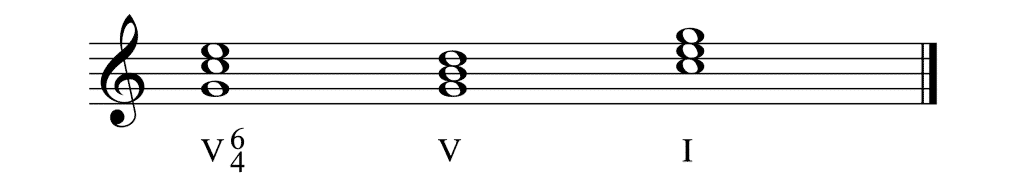

A cadential 6/4 is a type of perfect cadence. It has a I chord in second inversion (in C major, that’d be G – C – E) leading to a V chord in root position, before the cadential motion of V – I.

Although the chords are technically I64 – V – I, because that first I chord has a V as the bass note, it is often considered an extension of the V chord; and the chord progression would read V64 – V – I.

Here is an example from Mozart’s Piano Sonata no. 11 in A Major (the bar that ends with the repeat sign):

Summing Up Chord Inversions

Basically, because most chords have three or more notes, you can start the chord with any of those notes as the bass note, and build it from there. Which inversion you choose determines how the chord sounds and behaves.

That about covers most things you’ll need to know about chord inversions. We hope that you have found this article useful and helped you understand chord inversions better.